Nickel (Ni)

Key trends in the nickel market

In 2022, the nickel market moved into a surplus of 114 kt, or 4% of annual consumption (compared to a deficit of 172 kt in 2021). Historically, market surpluses have been linked to the LME deliverable / Class 1 nickel. However, in 2022, the surplus was mainly represented by the low-grade nickel units, particularly nickel pig iron (NPI) and FeNi. Meanwhile, the high-grade nickel market remained in deficit, particularly as nickel inventories halved in 2022.

After a year of significant deficit in the nickel market in 2021, which resulted in a 38% increase in the annual nickel price, the price started the year buoyantly as robust speculative demand and significant spot market tightness had caused exchange stocks to dwindle further. As a result, combined with logistical bottlenecks and geopolitical tensions in Eastern Europe, the price has been pushed to an 11-year high of USD 24,000/t in mid-January, although this price spike was somewhat speculative and was accompanied by massive short covering.

Source: Company data

In February, the nickel price dynamics were dominated by escalating geopolitical tensions between Russia and Ukraine, which was further exacerbated by the low exchange stocks. As a result, the LME nickel price increased to a new 11-year high of USD 30,000/t during the trading session of 4 March.

On 8 March, the LME was forced to suspend trading in all nickel contracts after prices jumped to a record USD 100,000/t, allegedly due to a massive short squeeze. Given the extreme price movements and low trading volumes, the LME decided to cancel all trades executed on 8 March and rewound the market to the moment when prices closed on 7 March.

The LME introduced new daily price fluctuation limits on nickel contracts based on the previous day’s closing price, allowed nickel position transfers, restricted the opening of new short positions, and resumed trading on 16 March. For several straight sessions, the price fell by the newly established daily limits, and the first settlement price of USD 30,800/t was recorded on 22 March only, but later on, prices steadied at around USD 33,000–34,000/t, albeit at low trading volumes.

The LME nickel price was in a downtrend in April–July, retreating after its enormous volatility and wild price swings. This downturn was further exacerbated by a broader trend of a demand slowdown across all base metals with the underlying weakness in the Chinese economy, strong US dollar and aggressive monetary policy tightening in conjunction with soaring inflation and attendant recessionary fears. On top of that, high energy prices and ongoing supply chain bottlenecks widely reduced investor activity across all markets and dented the industrial demand.

In July–September, nickel prices were rising, hitting a 3-month high of USD 25,000/t in late September, supported by increased sales in the EV market and low LME inventories, but lost all of the gains soon and plunged to USD 21,000/t in less than a week as the US dollar index hit a 20-year high, deteriorating the commodity prices.

In October, the price remained stable at around USD 21,000–22,000/t before surging to above USD 30,000/t in November. This has been caused by several factors, including speculation regarding the ban on the Russian metals by the London Metal Exchange and slower growth in the US CPI data, driving expectations that the Fed would ease the pace of its interest-rate increases with a correspondent drop of the US dollar index and a jump in prices of all major commodities. These price gains were also supported by the rumours about a possible Indonesian nickel export tax, an unconfirmed report about a blast at CNGR’s NPI-to-matte conversion plant in Indonesia, as well as disruptions at several nickel producing sites in Ukraine and New Caledonia. Later, however, the price retreated to USD 25,000–26,000/t.

In the first half of December, the nickel price rebounded to USD 30,000/t amid increased speculative trading, which could augur a new short squeeze attempt, but the price then retraced to USD 28,000/t. In late December, LME nickel prices stayed at USD 28,000–30,000/t in a sluggish market ahead of Christmas and New Year holidays.

Due to substantial volatility, the LME nickel price averaged USD 25,605/t in 2022, up 38% from the 2021 average.

Source: London Metal Exchange (cash settlement)

Source: London Metal Exchange

- Geopolitical tensions in Ukraine

- Massive short squeeze

- The LME suspends trading in nickel contracts and cancels all trades after prices doubled to a record USD 100,000/t

- Resumption of LME trading amid illiquid market

- Strike at Glencore’s Raglan nickel mine

- LG Energy Solution launches construction of extensive nickel sulphate, PCAMPCAM – Precursor cathode material.

and CAMCAM – Cathode material. capacities in Indonesia - US inflation at a 40-year high

- US President Joe Biden signs Inflation Reduction Act 2022

- Strike at Glencore’s Raglan mine ended

- DXY hits a 20-year high of 115

- The London Metal Exchange announces public consultation on banning Russian metal

- US inflation slows down to 7.7% following the DXY decline

- The London Metal Exchange decides against banning Russian metal

- Failed squeeze on low volumes, unconfirmed blast at CNGR’s plant, Goro’s leaks, and rumours about Indonesia’s export taxes

- The EU considers imposing sanctions against the Russian mining sector

Market balance

Primary nickel consumption grew by 5% y-o-y to 3.03 mln t in 2022. However, sluggish stainless steel production due to lower end use demand in China (on the back of the zero-COVID policy and a weak real estate sector) and in Europe (due to a wild surge in energy prices and inflation rates) was offset by a substantial increase in demand from the battery sector (up 32% y-o-y).

Primary nickel production totalled 3.14 mln t in 2022 (up 16% y-o-y). This increase was driven by the massive growth in the Indonesian NPI capacities (to 1.15 Mt Ni, or up 33% y-o-y) and the continued underlying growth of nickel compounds for the EV batteries sector, mainly fuelled by the launches of new HPAL capacities and NPI-to-matte conversion lines.

As a result, in 2022, the nickel market moved into a surplus of 114 kt, mostly in low-grade nickel. This was primarily due to lower-than-expected stainless steel output and a surge in NPI output in Indonesia, resulting in significant discounts for low-grade nickel and accumulation of NPI and FeNi stocks. Meanwhile, the high-grade nickel market saw a moderate deficit as evidenced by a decline in total nickel inventories of the LME and SHFE, which dropped by 49 kt in 2022 to 58 kt at the end of the year, or less than 10 days of global consumption.

Source: Company data

Consumption

Stainless steel remained the key sector of nickel use (about 65% of primary demand) in 2022. Adding nickel as an alloying element to stabilise the austenite structure enhances steel’s corrosion resistance, high-temperature properties, weldability, formability, and resistance to aggressive environments.

Stainless steel production uses almost all types of nickel feed (except for some special products, such as nickel powder and compounds). However, since the quality of nickel used has almost no effect on stainless steel quality, steelmakers primarily use cheaper low-grade nickel such as NPI, ferronickel and nickel oxide. As a result, the share of high-grade nickel used in stainless steel has decreased in recent years.

In 2022, global stainless steel output declined by 5% to 56 mln t as industrial demand in China was dampened by the government’s zero-COVID policy and stringent lockdowns amid continuing stagnation in the construction sector, which led to a drop in production in both China and Indonesia (by 2% and 4%, respectively). This was accompanied by a substantial decline in production in Europe and the US due to sluggish end use demand and rising energy prices, which translated to a jump in production costs. Consequently, output dropped by 16% in Europe and by 13% in the United States. Production was also stagnant in other countries around the world (Japan, South Korea, Taiwan). India was the world’s only country that ramped up its stainless steel output by launching new production capacities, with its output up 1%.

At the same time, primary nickel demand in the stainless steel sector stayed flat at about 2 mln t in 2022. The overall decline in output was offset by the growing demand for Indonesian NPI, the preferred nickel feedstock for integrated stainless steel producers in China, the world’s largest producer accounting for nearly 60% of global steel output. This led to a lower share of demand for scrap, i.e. secondary raw materials, and a corresponding increase in use for primary nickel.

The battery industry uses nickel as a key element in the production of cathode precursors for batteries. In 2022, nickel demand continued to rise and grew 32% to 468 kt, driven by global EV support policies, rapid expansion of charging infrastructure and battery cost optimisation.

Lithium-ion batteries are the key type of batteries because of their high energy density, specific energy and long life cycle. Growth in lithium-ion battery production is primarily driven by transport electrification. In 2022, EV sales (battery electric vehicles and plug-in hybrids) rose more than 60% to 11 million units, growing at a CAGR of over 50% between 2015 and 2022. The impetus for transport electrification comes from government incentives, more stringent environmental regulations, improved battery performance, and lower production costs of battery cells.

Source: Company data

Sources: Eurofer, ISSF, USGS, SMR, METI, TSIIA, Company data

Source: Company analysis

China was the epicentre of this growth, with its sales almost doubling due to higher availability of EVs across price segments and more robust consumer demand. At the same time, sales in Europe rose only by 11% y-o-y and even declined for some months, reflecting the increasing cost of living and the pressure on consumer savings as well as the rising expenditure on energy and soaring inflation.

The growing popularity of electric and hybrid cars, along with the evolution of cathode technology towards nickel-intensive types, add to the tailwinds for significant growth in primary nickel demand in batteries in the long run. Despite the mounting competition across technologies, high-nickel formulations will remain the preferred option for automakers owing to their higher energy density, longer range and better recyclability. In our base case scenario, we estimate the nickel use in batteries to reach approximately 1.5 mln t of nickel by 2030, or 30% of total primary nickel demand (compared to 15% in 2022). Meanwhile, this figure may require further revisions given the continuous introduction of more ambitious carbon neutrality goals, subsidies-driven transport electrification and cost optimisation of battery cell production.

In 2022, nickel consumption in other industries (alloys and superalloys, plating, special steel) increased by 8%, or 43 kt, amid the gradual post-COVID recovery of industrial demand and robust economic performance in the aerospace, oil and gas, and military industries.

Production

Source: Company data

Source: Company data

Primary nickel production can be divided into the high-grade and low-grade nickel segments.

High-grade nickel is produced in the form of nickel cathodes, briquettes, pellets and powder, rondelles, and other small shapes, as well as chemical compounds, both from sulphide and from more common and available lateritic raw materials. 2022’s leading producers of high-grade nickel were Nornickel, Jinchuan, Glencore, Vale, BHP, and Sumitomo Metal Mining (SMM).

Low-grade nickel includes nickel pig iron, ferronickel, nickel oxide, and utility nickel, which are produced from lateritic raw materials only. In 2022, the key producers of low-grade nickel were Indonesian and Chinese NPI smelters, such as Tsingshan Group and Delong Group, as well as the largest ferronickel producers: POSCO, South32, Eramet, Anglo American, etc.

The nickel market, which had been fundamentally divided into the low-grade and high-grade segments, became interconnected once the practical implementation of the NPI-to-matte conversion started in early 2021 along with the massive launches of HPAL capacities.

In 2022, producers around the world were faced by both geopolitical upheavals, energy crisis, operational disruptions, and pandemic-induced challenges. Nonetheless, primary nickel production in 2022 grew by 443 kt, or 16% y-o-y, to 3.14 mln t, driven by the huge growth in the Indonesian NPI capacities and the continued underlying growth of nickel compounds for the EV batteries sector, mainly fuelled by the launches of new HPAL capacities and NPI-to-matte conversion lines.

Production of high grade nickel grew 14%, or 135 kt, to 1.1 mln t in 2022.

Production of nickel metal rose 5% y-o-y to 817 kt. Nickel metal production in 2022 was slowly recovering, although several major producers reported some downturns in their output because of strikes, operational issues and rising costs on the back of the energy crisis.

For instance, Vale’s Copper Cliff pellets and powder production in Canada grew year-on-year, while Long Harbour’s rondelle output declined. In turn, the output of pellets and powder at the UK Clydach plant declined year-on-year due to the lower availability of PT Vale Indonesia’s matte.

Glencore reported a lower production of cathodes and rondelles in 2022 because of the strikes at its Nikkelverk refinery in Norway and at Canada’s Raglan mine (both conflicts are now resolved). The company, however, increased its production of briquettes and electrolytic powder at its Australian Murrin-Murrin plant after numerous operational disruptions in 2021.

In 2022, Australian BHP’s briquette and electrolytic powder production decreased due to equipment maintenance on the back of the switch from briquettes to nickel sulphate crystals production, gradually rising following its launch in late 2021.

Japan’s SMM demonstrated weak results in 2022 due to feed shortages and some operational issues in the Philippines, which adversely affected HPAL operations (Taganito and Coral Bay) that feed the Japanese refineries of SMM.

Meanwhile, Ambatovy continued ramping up briquette production in 2022 in order to achieve stable operation levels of 40 ktpa of nickel.

In 2022, Nornickel increased its nickel output as a result of postponing the repair of the flash smelting furnace at Nadezhda Metallurgical Plant to 2023 and the low base of 2021, when Oktyabrsky and Taimyrsky Mines as well as the Norilsk Concentrator were temporarily suspended.

Production of nickel compounds, including nickel sulphate from primary sources (excluding sulphate produced by Class 1 nickel dissolution), increased by 81% y-o-y to 378 kt in 2022 on the back of the massive launches of new NPI-to-matte conversion capacities and announced launches and ramp-ups of new and existing HPAL capacities in Indonesia, Australia and New Caledonia. This was caused by robust EV sales and solid nickel demand from the battery sector.

Nickel sulphate can be produced from a variety of raw materials by different processes: directly from nickel intermediates such as mixed hydroxide precipitate (MHP), mixed sulphide precipitate (MSP), nickel matte, and crude nickel sulphate (product of copper processing), or by dissolving Class 1 nickel (as nickel briquettes or powder) or from recycled materials.

In 2022, the expansion of HPAL capacities launched by Lygend and PT Huayue Nickel and Cobalt in 2021 as well as the launch of a new PT QMB New Energy Materials asset drastically increased total MHP output in Indonesia compared to 2021, approaching 100 kt. Huayou’s fourth project, PT Huafei, is expected to be brought online in 2023, accompanied with the expansion of existing capacities, which will further boost MHP output.

Meanwhile, the waste generated by HPAL projects is becoming a severe limiting factor in terms of potential environmental effects as well as costs required to ensure their safe storage. According to CRU, if all Indonesian HPAL tailings were dry-stacked, the total electricity consumption to achieve that would exceed 300 GWh, primarily through coal combustion. For comparison, it is about 10% of the Greater London’s current total electricity consumption. Moreover, this waste will require haulage resulting in nearly 40 million litres of diesel consumption, too.

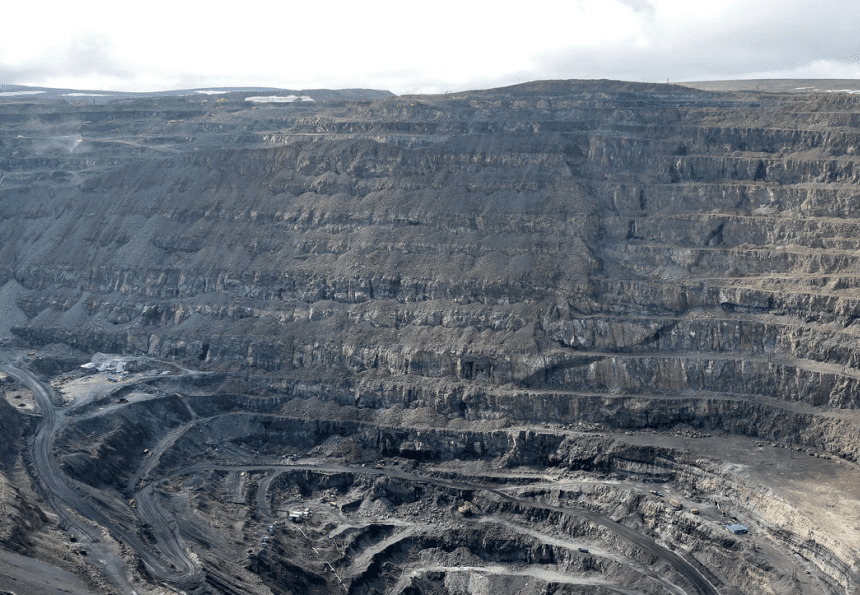

In general, laterite mining is associated with substantial damage to ecosystems, including deforestation, lower biodiversity, groundwater contamination as well as soil and coastal erosion.

Low-grade nickel output grew by 18%, or 308 kt, to 2.0 mln t.

Indonesian NPI production continued to grow year-on-year, becoming the key driver behind the low-grade nickel supply growth in 2022. However, its growth rates slowed down slightly year-on-year due to both conversion of some furnaces to high-grade matte production and softer demand for stainless steel as well as skilled labour shortages in Indonesia. In addition, strict COVID regulations and more expensive airline tickets made travelling to these projects less attractive for Chinese workforce. Overall, we estimate the total 2022 NPI production in Indonesia at 1.1 mln t (up 33% y-o-y).

In 2022, China’s NPI output was down 1% y-o-y to 421 kt suppressed by stronger imports of Indonesian NPI and stagnant stainless steel production. Nickel ore imports from the Philippines were down due to bad weather conditions, which kept ore prices high, putting additional pressure on the NPI production.

During the year, FeNi production declined substantially to 341 kt (down 10% y-o-y). This was due to production shutdowns across several sites, including facilities in Serbia, North Macedonia, Greece, and Ukraine, as well as technical and operational disruptions at projects in Myanmar, Guatemala, Japan, and New Caledonia. On the other hand, a number of producers in New Caledonia, Brazil, the Dominican Republic, and Colombia were able to ramp up their output and deliver consistent performance. The surplus in the low-grade nickel market resulted in significant discounts for FeNi and accumulation of its stocks.